Here I tell you what I mean by “strategy” and how I do it. Examples, especially in public policy, are on my personal web site.

What is strategy?

Is there any consultant that doesn’t claim to provide “strategic” advice?! But how many really do?

I find the word “strategic” is so misused that it’s in danger of becoming meaningless. So I will tell you what I mean by it (borrowing from the experts):

Strategy is about what race you run, not how fast you run.

(This is a more succinct statement of what Michael Porter says here about providing a unique and valuable market offering, rather than competing on cost with others producing the same thing.)

- It’s not about using Total Quality Management (TQM), benchmarking, and re-engineering etc to improve quality, reduce costs by 10% and double profits (as important as this is – and I can help with that sort of optimisation analysis too), because competitors can and will quite easily do the same things.

- Strategy is about understanding your strengths vs those of your competitors and the opportunities and risks in the market (or all markets), so you can make a decision about what products/services to specialise in (& which not to), so you face the least competition. Yes, the paradox of competitive markets is that the most successful participants are those that create a niche monopoly for themselves! How else will a company and its employees find the spare time and money to think, innovate and be motivated to stay ahead of the game? Competing on cost is a mug’s game!

So, a genuine strategy requires two key things:

- Integrated problem-solving – optimising the whole, not just the individual parts, based on an understanding of all the interrelated things affecting your organisation & market sector, i.e. how each affects the other and the total. A big investment decision is not “strategic” simply because it’s big; it is only truly strategic if it positively reinforces other components of business operations & strategy, and does not detract resources from better projects…

- Necessarily, it requires focus and choices, often difficult ones, especially about what not to do, or what to stop doing, as there are always good arguments and strong and conservative or vested interests backing existing activities (as the book, “Good Strategy, Bad Strategy” describes). In simple terms, it means “focus on what you’re good at” and it inevitably involves taking risks – preferably informed ones! So effective strategies require good judgement and great leadership.

A strategy to do everything is no strategy at all – which is the most risky path to take, and very common in the public sector, where politicians want to be all things to everyone!

In my view, strategy is just as important for nations as for businesses in a globally competitive economy (especially small nations, which don’t have the scale to do everything well), which means that contrary to advocates of “laissez-faire markets”, governments do actually need to “pick winners”.

It’s the network, stupid!

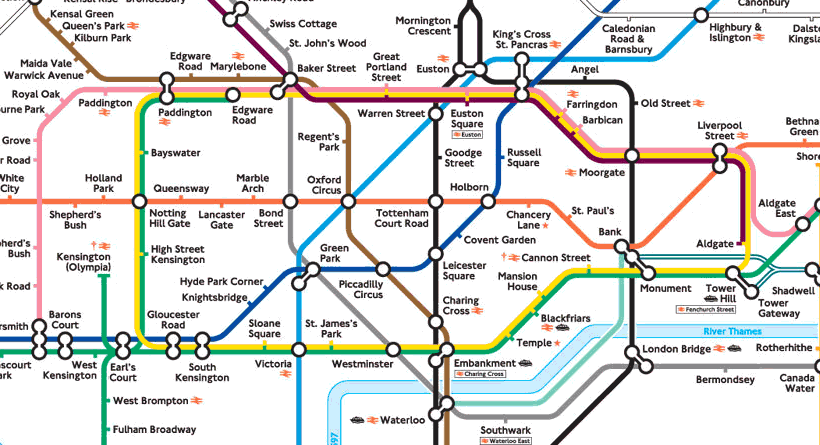

Since strategy is all about how everything connects and interacts together, it is especially important in traditional network industries like transport, telecomms & energy, where network interconnections make the whole far greater than the sum of its parts. For example, a phone exchange enables just one wire from your phone to connect to any other phone on the planet, and the fundamental feature of the classic London Overground network is the interchange between lines that enables a fairly limited number of lines to provide travel from anywhere to anywhere.

One of the most complex and badly-done areas for strategy is metropolitan city planning, as this requires simultaneous consideration and optimisation of transport networks, housing, leisure, public services, business activity/agglomeration centres, economic drivers, financial/public-sector fiscal constraints, and even interactions with housing & business activity in regions outside of the metro area (so basically, optimised human living!).

Perhaps less obviously, linkages between business are becoming increasingly important for all industries in the new “network economy” (especially “Fin-tech”), because as the pace of change & innovation continues to increase in society, the most efficient businesses are relatively small, specialised and nimble (so they can excel in their niche and respond rapidly to change), but to be successful they then need to form partnerships/networks with other businesses so they can provide complete, integrated solutions to clients (without doing everything themselves).

Think ahead!

Strategic metro planning also involves long time frames (decades) and therefore significant uncertainty, risk & future opportunities/options (known & unknown), which a strategy needs to influence yet also be flexible to respond to (because a strategy is not a rigid, geographic “plan”, as many urban & transport planners wish). But it needs to have this flexibility without becoming a neutral/do-nothing strategy. These challenges of thinking ahead and pursuing a flexible strategy that has multiple, mutually supportive component actions are of course fundamental to the quintessential strategy game of chess.

How do I do strategy?

So, I hope the above convinces you I know what strategy is, which I think is an important precondition for doing it well! But why else am I good at it?

Well, quite simply, I’m lucky to have the sort of brain that is excellent at recognising patterns & making connections or identifying inconsistencies. And this matters because the scope of strategy is so broad that it’s not something that can readily be solved by advanced computer modelling. In fact, the more sophisticated the model, the more it needs to be built around a certain view of how the world works, which necessarily constrains it to a specific strategy, and most likely, existing practices. Thankfully there is still a role for the human brain! Or better still, many brains, which brings me to my approach:

1. Gather information & identify “the problem”

The first thing I will do before I ponder a new strategy is talk to you and as many other people as I can, so I can understand as much as possible about the totality of the problem that needs to be solved. Often this requires some deep thinking about the interactions in the system to identify the “root cause” problem, which is different from the symptoms that may be superficially presented as the problem. Once the root-cause problems are identified, the solutions are commonly almost obvious.

2. Think

I’ll then spend time thinking – a lot; all the time, day & night! This is how my brain tries to make sense of everything & solve problems – working out how it all fits together, what the patterns or inconsistencies are and what the “solution” is that nicely reconciles all these factors.

Please don’t pressure me – it won’t help. Lack of time to think (plus change-resistance) is often why existing management find it hard to develop an effective strategy. If you’re trying to develop a strategy at the last minute then I’m afraid it’s not a good sign. I’ll always do my best but try to engage me before you’re in a rush!

3. Hypotheses analysis

As I start to develop a clearer idea of the problem(s), I’ll begin to develop one or more potential hypotheses about what matters most and what the solution might involve, which I’ll typically test with some simple analysis. Sometimes this will quite literally be back-of-the-envelope calculations, because for strategy it’s more important to work out what’s most important (& critically, what isn’t) than to calculate all parameters accurately. Sometimes, however, the problem might need more complex maths, simulation or optimisation.

4. Iterate

I will then iterate the process – checking and refining my developing thoughts and assumptions with more analysis, data research and discussions with you. That will include understanding the real-world obstacles to change, as whilst I won’t shy away from radical reform because “it’s too hard” (scary), I do recognise that barriers exist, so in my way of thinking they are simply part of the problem to be solved. Any fool can offer a great solution by ignoring undesired constraints, but I prefer the challenge of more difficult, constrained problem-solving!

5. Present

Finally I’ll present my analysis and recommendations as simply and concisely as I can. My public sector experience has taught me to present advice in one or two pages – otherwise it won’t be read or heeded! Also I like strategic solutions to be elegantly simple, and communicated that way as far as possible. The CEO needs to convey the strategy so it is understood and almost instinctively followed by everyone, and that’s not going to happen if the answer comes out of a complex “black box” computer model and a 100+ page report!